A while ago at work we were discussing the pros and cons of the classic Linux profiler gprof…

What are profiles useful for?

- Profiles allow you to observe what a program is doing at runtime without runtime access to the source code (although source is needed to build a profile-enabled binary).

- A performance regression or improvement in a given program will often show up in a profile as a change in either duration or number of calls to some set of functions that changed between software builds.

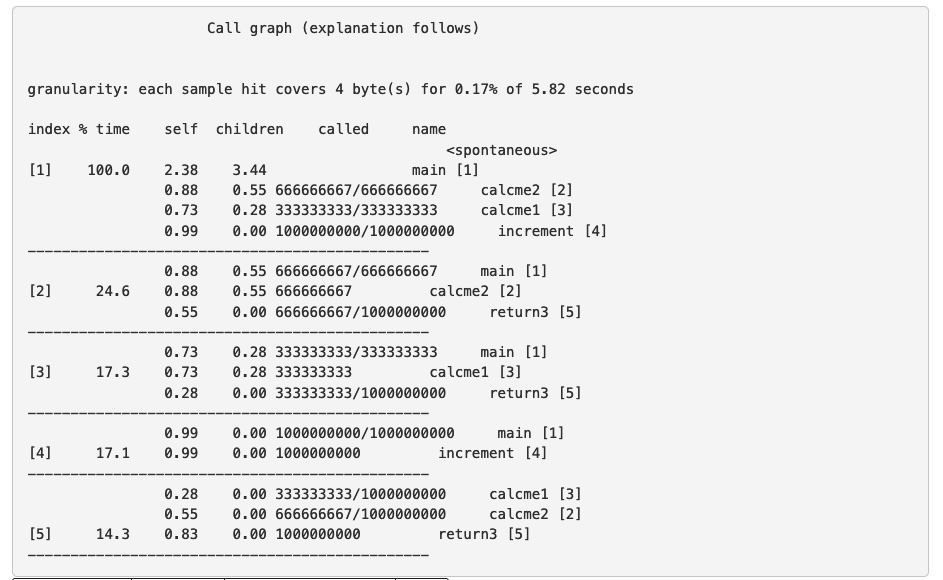

The output of a profile run against a very simple program looks like the example below.

Call graph (explanation follows)

granularity: each sample hit covers 4 byte(s) for 0.17% of 5.82 seconds

index % time self children called name

<spontaneous>

[1] 100.0 2.38 3.44 main [1]

0.88 0.55 666666667/666666667 calcme2 [2]

0.73 0.28 333333333/333333333 calcme1 [3]

0.99 0.00 1000000000/1000000000 increment [4]

-----------------------------------------------

0.88 0.55 666666667/666666667 main [1]

[2] 24.6 0.88 0.55 666666667 calcme2 [2]

0.55 0.00 666666667/1000000000 return3 [5]

-----------------------------------------------

0.73 0.28 333333333/333333333 main [1]

[3] 17.3 0.73 0.28 333333333 calcme1 [3]

0.28 0.00 333333333/1000000000 return3 [5]

-----------------------------------------------

0.99 0.00 1000000000/1000000000 main [1]

[4] 17.1 0.99 0.00 1000000000 increment [4]

-----------------------------------------------

0.28 0.00 333333333/1000000000 calcme1 [3]

0.55 0.00 666666667/1000000000 calcme2 [2]

[5] 14.3 0.83 0.00 1000000000 return3 [5]

-----------------------------------------------It tells us that of the 5.82 seconds of profiled runtime

2.38seconds were spent inmain()3.44seconds in functions called by main (either directly or indirectly).

It also tells us that the function return3() was called 1,000,000,000 times

- 1/3 by

calcme1()and - 2/3 by

calcme2()

Profiles can give a good overview of where time is spent – albeit with some overhead.

In the profile outputs, the number of calls is exact but the time spent is the result of sampling. So the relative time spent in the functions should be correct, but the absolute time will normally much lower than the runtime/execution time reported by e.g running $ time <some-binary>

generating a profile for gprof to use

There are three pieces to using a profile

- ask

gccto insert additional code (a function call to__mcount) into the compiled binary - ask gcc to tell the kernel to keep track of where the program counter (PC) is running whenever it is sampled (

__monstartup) - use the

gproftool to process the output.

There is no need for any special hardware support – profiles run fine in a VM/container etc whereas some tools need to access the CPU directly via pass-through, or you need to be root etc.

The general workflow is as follows

Build a binary using the flag -pg this will create a “special” build of your program which implements profiling – the program should operate as normal, albeit a bit slower. the implementation of profiling is detailed here in the gprof man/help/doc page. I will cover the overhead of profiling in a separate article.

There will be a additional symbols/function inserteds into the binary that gcc produces. In the output of nm you will see these functions – mcount/monstartup.

These functions do the work of figuring out which function calls what and how long each function runs fo – so an easy way to see if a binary has profiling enabled is to look for those symbols.

During compilation/linking gcc inserts calls to mcount into each function call in the assembly/binary that it produces for you. monstartup is called once at the beginning of the program.

How to determine if a binary has profiling enabled

In the output below the symbol counter is just a variable in my program.

gary:~/git/unixfun/simple-call$ cc -o 1b-pg -pg simple_call_1B.c

gary:~/git/unixfun/simple-call$ nm ./1b-pg |grep count

0000000000004018 B counter

U mcount@GLIBC_2.2.5 <----- This binary has profiling enabled

gary:~/git/unixfun/simple-call$ cc -o 1b simple_call_1B.c

gary@perflabjump:~/git/unixfun/simple-call$ nm ./1b |grep count

0000000000004014 B counter

<------- No mcount, means no profilingHow is the profiling actually achieved?

In the assembly you will see calls to _mcount. To see the ASM produced, you can use objdump -d Here is part of the output from objdump -d <binary>

1242: 53 push %rbx

1243: ff 15 9f 2d 00 00 call *0x2d9f(%rip) # 3fe8 <mcount@GLIBC_2.2.5> <----- this is only seen in pg builds

1249: bb 00 ca 9a 3b mov $0x3b9aca00,%ebxGenerating and Reading the profile

- Run the binary compiled with

-pgit will create a binary output file calledgmon.outin the current working directory. - Use the

gproftool to read the gmon.out – it needs to reference the binary (compiled with pg) to show the right symbols/functions etc. In our example below for the binary compiled with profiling. - After the run completes – issue

gprof 1b-pgand the gprof command will read the file gmon.out and use the symbols in the binary to display the correct function names.

The output of gprof

The output of gprof is just a text file containing information on the program as it ran – you can read it with a standard text editor. You are looking for the profile section. There are two main sections, the Flat Profile and the Call Graph e.g. something like this:-

Flat profile:

Each sample counts as 0.01 seconds.

% cumulative self self total

time seconds seconds calls ns/call ns/call name

40.98 2.38 2.38 main

17.10 3.38 0.99 1000000000 0.99 0.99 increment

15.12 4.26 0.88 666666667 1.32 2.15 calcme2

14.26 5.09 0.83 1000000000 0.83 0.83 return3

12.54 5.82 0.73 333333333 2.19 3.02 calcme1